Born into a poor family of 13, in the village of Karim Sudan in 1966, there was very little chance of Hussein becoming an artist. He was expected to pursue a stable income, and regular career. Convincing his father that he had a talent worth pursuing was a challenge, and the Village in which he grew up was both a cultural and an actual desert. There was no access to books, nor images of art. It seems almost impossible for someone to have grown up in this environment but still have an ambition to be an artist.

As He says: “I grew up surrounded by emptiness. Total emptiness. I never saw an apple until I was seven years old. I knew they existed but didn’t know what it might look like. Is it square? Does it have stripes? That kind of emptiness and poorness allows us to imagine things because we don’t have it in front of our eyes.”

This absence of visual references fed his imagination and his desire to draw but it also set him on a path to abstractionism that has been a hallmark of his artistic practice ever since.

The other battle Hussein faced as a young artist was a financial one. To remain in art school and buy materials he had to sell his art straight away. He discovered that the Sudanese do not value art, making it very difficult for him to move forward.

“To be an artist in Sudan is a sin – a social sin, a mistake. We had a fundamental Islamic regime holding power and marry that with a bad economic situation. We had a good school of Arts, but it is being demolished day by day. That place is seen as the Devils place in the fundamentalist regime mindset.” He observes.

A sale to a Foreign Embassy staff member led a German Art dealer to his home – this meeting led to a touring exhibition in Germany in the late 1990’s.

The success of this exhibition made Hussein reluctant to return to his home country which had few supporters of the arts. Thus began his search for a more suitable home, moving around Europe, and selling and exhibiting his art. He realised that he wanted to settle in a warm, English-speaking country. A welcoming official at a South African Consulate convinced him that South Africa may be the best place for him.

In 2004, he settled in Pietermaritzburg with his artist wife and two children, and his work has found great acceptance from the local art collecting community, with a number of top Galleries hosting his works and exhibitions to great success.

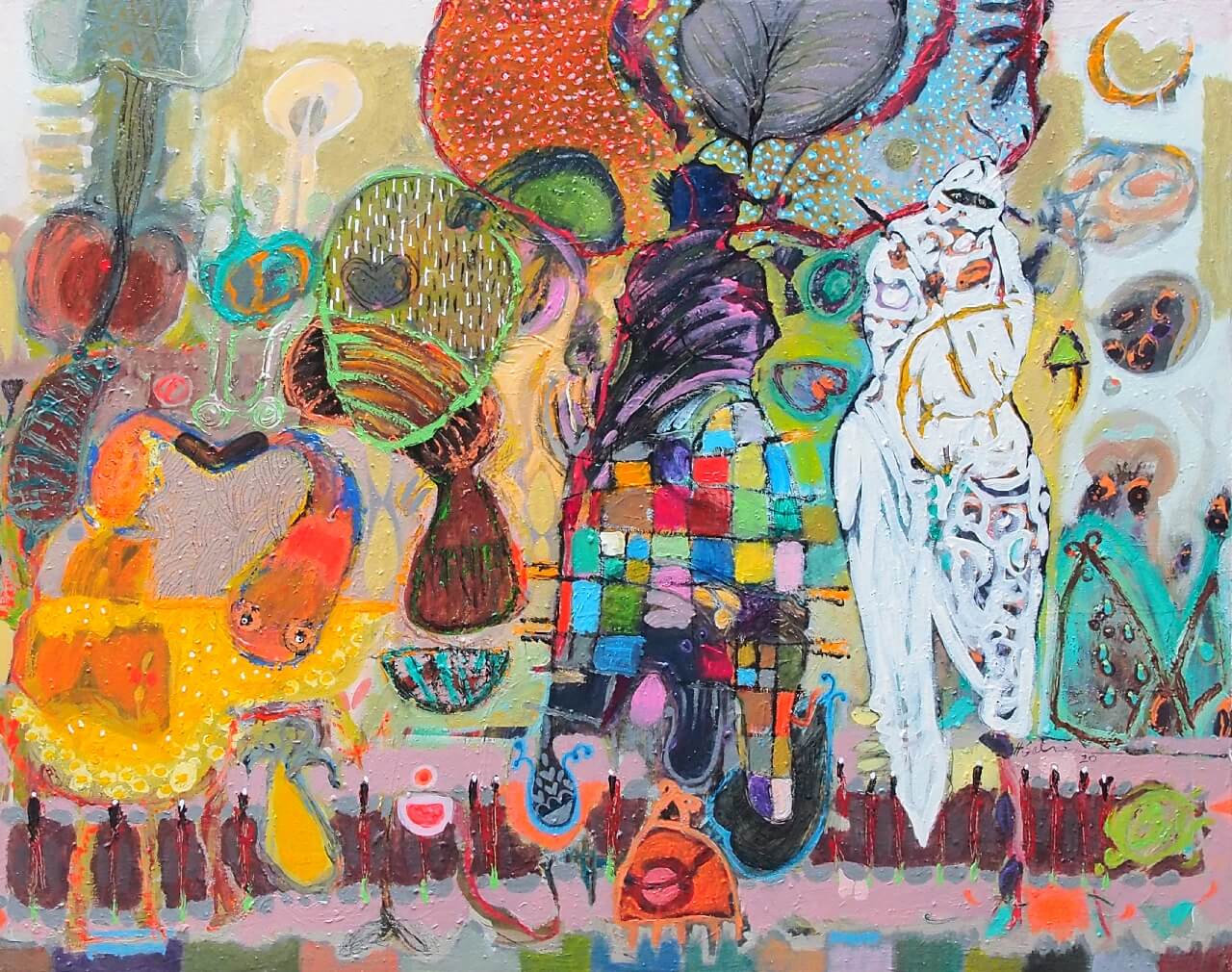

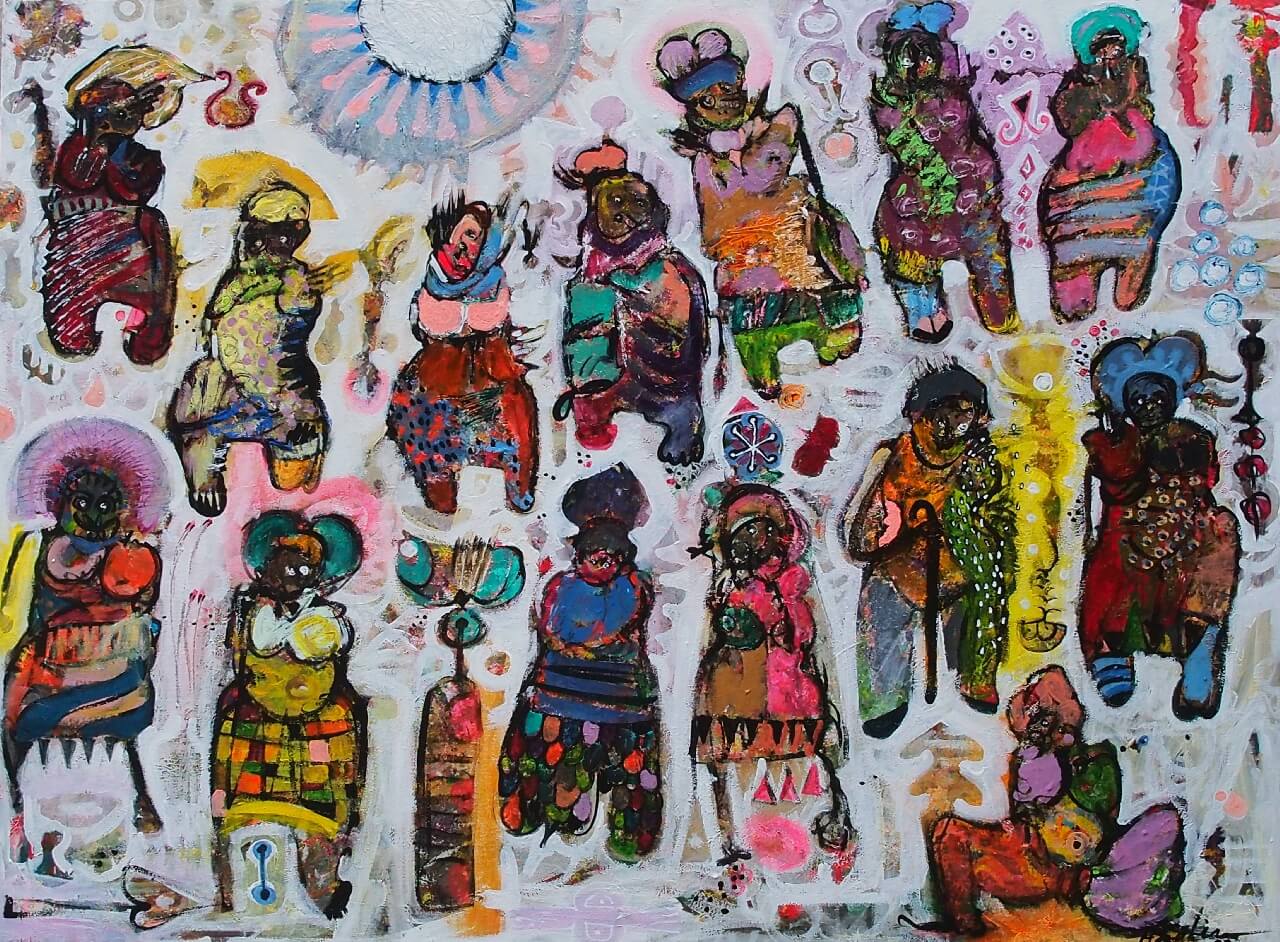

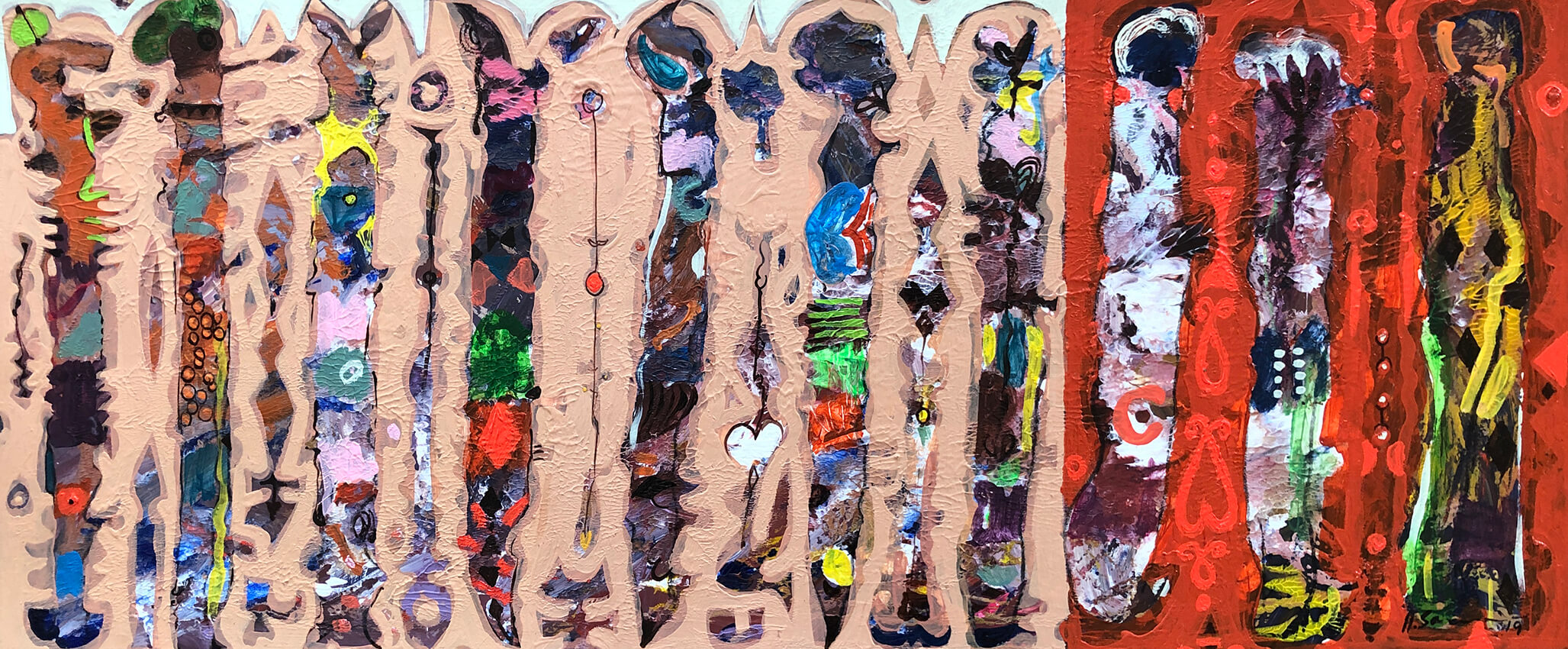

Being an artist is intrinsically going to be tied to a narrative of survival and” finding your place in the world”, says Hussein. He has found that place, via an aesthetic defined by the multitude of cultures he has encountered in his worldly travels. His work contains the colours and patterns, motifs and symbols he has found in all the different cultures that he has experienced.

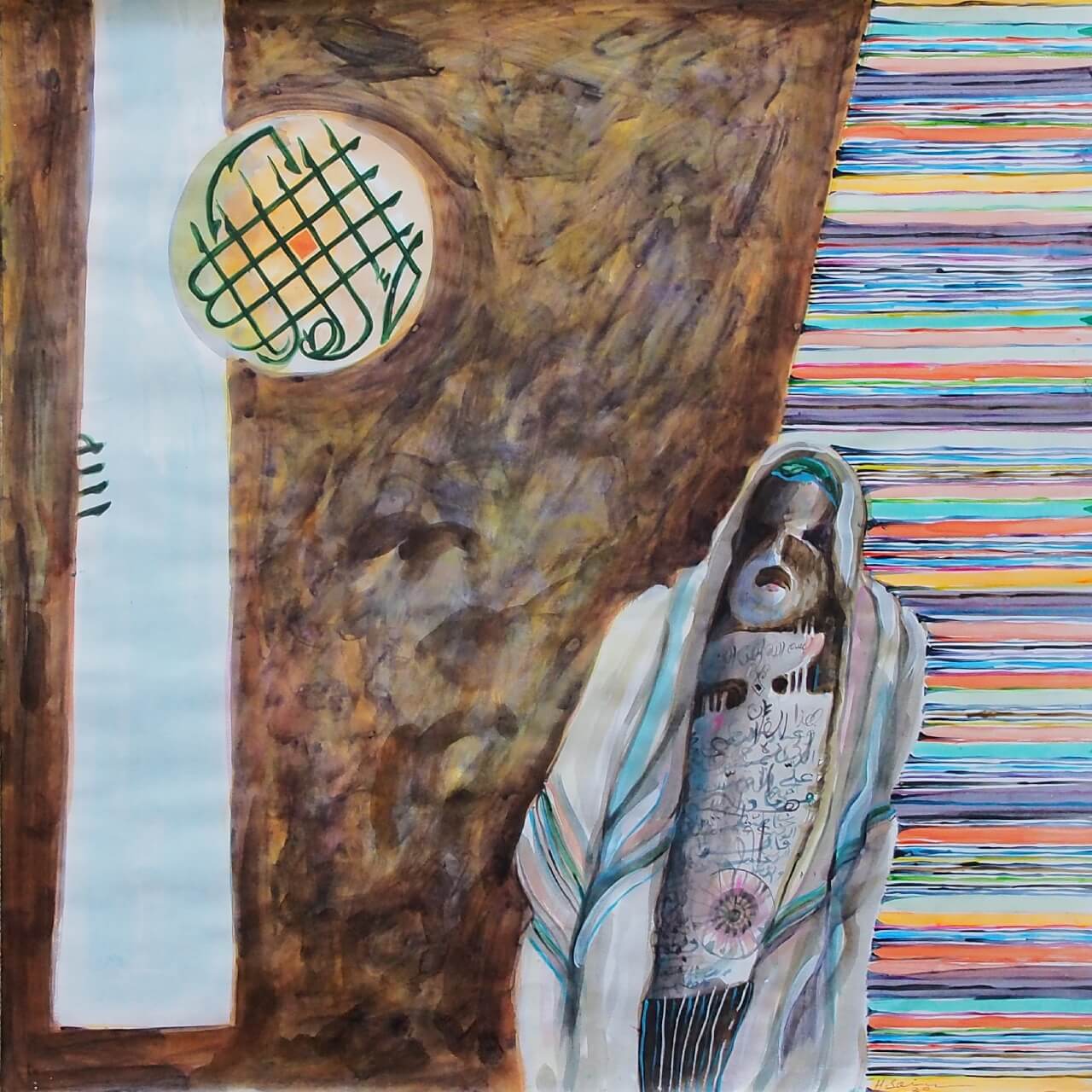

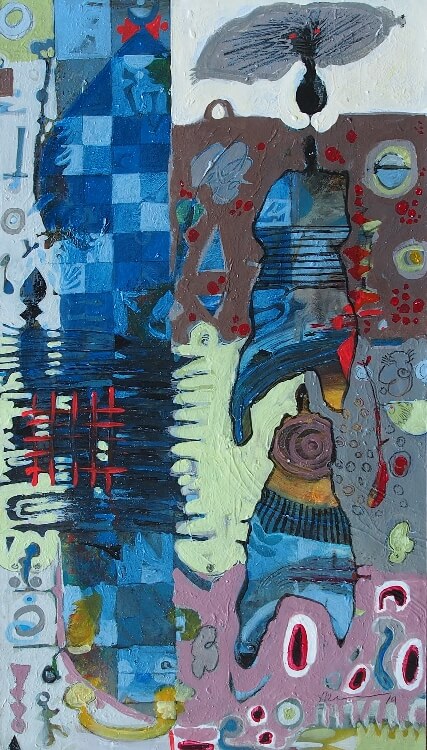

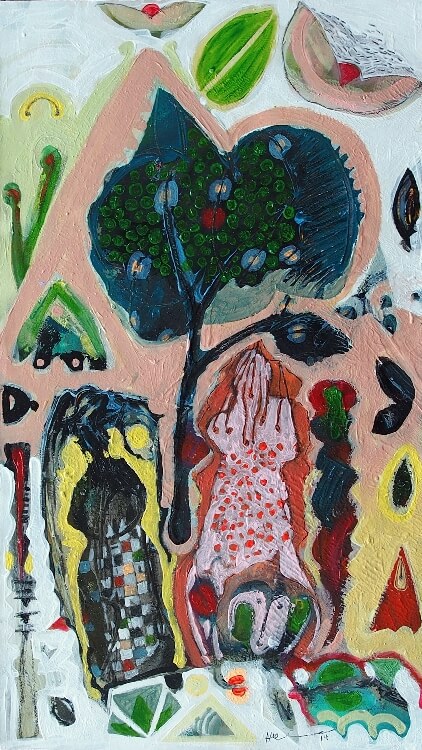

His paintings express a vivid intensity that demonstrate his accomplished and adept familiarity with the medium. His forms and colours combine, symbolising his own psyche and subliminal musings on topics of identity and heritage in the contemporary discourse. However, what is critical is that the shapes and forms in his work only leave just enough clues to catalyse thinking rather than explicitly demonstrate an idea. The busyness of each work requires quiet contemplation, asking the viewer to juxtapose the noise of the world with the act of quiet introspection. Using a number of recognisable painting techniques, the works evoke a sense of layered anticipation and a multiplicity of influences. This speaks back to his grappling with identity and impact of art within the context of his life. The paintings have been described as landscapes in themselves, mass grids of engaged surfaces, in which worlds and societies can exist.

As a contemporary African artist, Salim is faced with the weight of art history and political discourse as equally pertinent to his formation as a voice within the conversation of makers. As such, Salim gestures to the work of other painters but also to history, culture, mythology and situation. His work contemplates the ordeals of human life, returning again and again to symbols of love, time and death. Another recurring motif is his veneration for the African Woman, this as a result of his enduring deep love and respect he has for his mother who succeeded against all odds to educate, feed, love and nurture him and his siblings.